What exactly is a RESTful Service? REST is an acronym for REpresentational State Transfer. It is a way of representing the data requested of, or sent to a web service in such a way that the server understands exactly what is being requested or sent, along with what the server should do with it and what it should send back to the client.

What exactly is a RESTful Service? REST is an acronym for REpresentational State Transfer. It is a way of representing the data requested of, or sent to a web service in such a way that the server understands exactly what is being requested or sent, along with what the server should do with it and what it should send back to the client.

What Exactly is State?

State, in terms of web applications, is what defines the current status or state of an object or control.

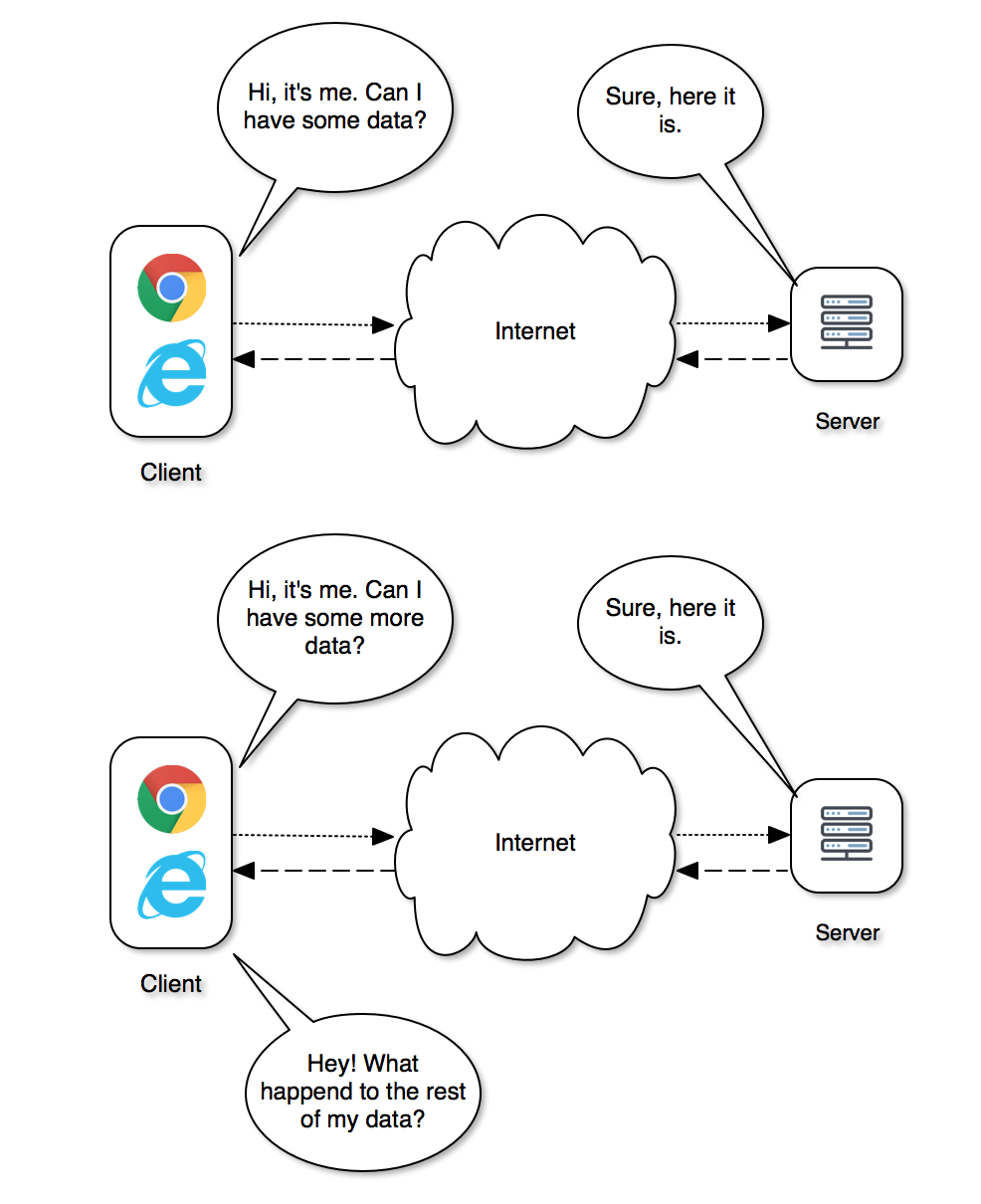

So, that’s clear as mud, right? Let’s first take a look at how browser-based applications actually work. First, there’s the browser, or client, but the browser is actually ignorant about the application. It must first establish communications with a web server. The web server is where the application actually lives.

When the client contacts the server, the server only knows about the client for the duration of that individual request to the server. Once the server sends the response back to the client, the server forgets about the client. This is why the web is known as a stateless environment.

This is more evident with forms-based applications where the user completes part of the requested data and initiates another call to the server for more information. If the client does not track the changes to the controls on the page, and if the server has no knowledge of the state of the controls, i.e. what’s been entered or selected, then the server might send back a fresh copy of the page to the client and all of the user’s work will have simply vanished.

For developers new to web application development, this can be very frustrating, especially if they come from a desktop development background where the state of the application’s controls are rigorously maintained. Modern web browsers have the ability to maintain the state of controls during subsequent calls to a server through what is known as Session State, but this is a costly feature and most developers disable it for their applications to improve performance.

With Session State enabled, the state of the browser’s content is converted to a hashed representation of the page and included in the body of the request to the server. The larger the web page that is sending the request, the larger the amount of data sent back and forth will be, and the server will require longer to start processing the request because all of that data must be converted, stored and then written back to the response to send back to the client. This is an extremely costly operation for most web browsers and servers depending on the size and complexity of this data.

So, how exactly do developers maintain the state of controls in the browser? Well, there are multiple ways to do this. Some are better than others, but the most efficient ways usually involve discrete calls to the server, requesting information, then updating the controls with the results from that service request using things like JavaScript.

This is where RESTful services come into play, but web browsers are not the only type of clients that can send and request data to and from a server. Clients can exist in browsers, desktop applications, mobile applications, and even other server applications. In fact, it’s quite common to integrate web service calls into other web applications to serve data to the client, acting as a proxy between the client and some external or third-party service.

What Makes a Web Service a RESTful Service?

In the early days of web services, developers created services known as XML Web Services, or SOAP services. SOAP is acronym for Simple Object Access Protocol, and is still widely used by a variety of companies today, although the popularity of SOAP is waning. It uses an XML structure for communications, and can be quite verbose, or wordy, leading to poor application performance. It also defines the specific methods that can be called to request or manipulate data through a series of contracts. The client must be aware of these method definitions by implementing something known as an Interface definition.

These Interface definitions are known as contracts, because they define what can and cannot be done with the service. The contracts are implemented on the client through proxyclasses, but if the service ever changes the contracts, the contract is rendered obsolete or broken, and a new contract must be established along with new proxy classes. The beautiful part of web services is that communications can take place using the HTTP protocol.

All of this might seem like a lot of work, and it was definitely not a trivial process, but it was major improvement over what developers refer to as a client-server infrastructure, which generally speaking, required a closed communication network and specific protocols and security measures unique to the network connections used or application.

Developers today prefer SOAP’s modern cousin, RESTful web services. The communications still take place over an HTTP protocol, but the service is more stateless and data and objects are usually requested using URLs that define the objects. The URLs, or Uniform Resource Locators need to be structured in such a way that the server can infer what is requested based on the structure of the URL. The URL represents the state of the objects being transferred.

There are many web services in use today that call themselves RESTful services that are not truly REST compliant. If you cannot infer what is being requested by the request’s URL, then there’s a pretty good chance it’s not truly a RESTful web service.

Defining a RESTful Service

For the purposes of this discussion, we’ll limit our discussion to the service itself and not the web servers they run on. Each service call requires a route, which defines the controllerand action, or method specific to the request. The route is essentially the URL of the requested action. The action is the method contained within a controller class.

I find it helpful to think of RESTful web services vs SOAP services in this way: SOAP services are method-centric, but RESTful services are object-centric. In other words, SOAP services are organized by task and RESTful services are organized by object. For example, with a SOAP service, we might have an area of our application that involves a department or organizational group.

Let’s use Human Resources, or HR, as an example. The SOAP service might be organized to serve data specifically related to HR services and data. We might end up with URLs that look like ‘https://someaddress.com/hr/getemployeelist’, but with a RESTful service, that URL might look more like ‘https://someaddress.com/employees’. The SOAP service would be centered around HR functions, but the RESTful service gets right to the subject matter requested: employees.

RESTful services also operate using standard HTTP verbs. Verbs in HTTP, like verbs in written and spoken languages, define an action. HTTP verbs used with RESTful services are GET, POST, PUT, PATCH and DELETE. Each verb describes the type of action being requested of the service.

- GET – used to retrieve an object or list of objects from a server. Serialized representations of objects are returned to the requesting client. GET calls should be idempotent, meaning that multiple calls to the same resource on the server will result in exactly the same results until another call is made that alters the persisted record.

- POST – used to notify the server that an object should be persisted or saved to the server. The object is serialized and included in the body of the request, and once saved, the object is serialized and returned to the requesting client.

- PUT – used to update an existing record on the server. Like POST requests, the serialized object is included in the body of the request.

- PATCH – like PUT requests, PATCH is used to update specific portions of an existing record on the server. Unlike PUT, only the portions of the record that have changed are included in the body of the request.

- DELETE – requests to delete an existing record on the server. The identifier for the record is included as part of the requests’s URL. Generally speaking, DELETE requests and responses do not include the objects themselves.

Controllers are usually structured around the objects they represent and the actions are normally based on a persisted record’s basic CRUD functions: create, read, update and delete.

HATEOAS

RESTful service guidelines are merely a set of rules that a service should be built around. One such guideline is the inclusion of a series of links in the serialized objects returned to the client. Because some requests can result in very large amounts of serialized data being returned to the client, it is often advantageous to not include child, or related objects in the initial response. The client application might not even be interested in those child objects. Therefore, an array of links can be included that point the client to other actions they can take on an object such as retrieving other related objects, as well as updating and deleting objects. This keeps the response time down and is known by the acronym HATEOAS, or Hypermedia As The Engine Of Application State.

When a client receives the response from the server, an array of URLs can be included as a ready reference so the client knows how to perform related actions on the objects returned from the server.

Wrapping it All Up and Further Reading

The topic of RESTful services is a very broad one, and I’ve only touched on a few highlights in this document. Microsoft has many resources regarding the design of effective REST APIs. One of the best resources I’ve come across is this article. Of course, there are many others as well.

I strongly encourage anyone designing or developing a RESTful API service to examine some of the many useful resources available. There is definitely no shortage of helpful information out there.